An interrogation of the intersection of crime and sex in Shakespeare’s Macbeth

The entire plot of Macbeth centers around the crime of murder being committed, however whilst it is easy to condemn Macbeth himself, it could be argued that both Lady Macbeth and the witches also have a role to play in it. Walter C. Reckless and Barbara Kay coined the phrase ‘the Lady Macbeth factor’ in 1967 in order to explain their argument that ‘women commit less crimes, but play an important part as instigators of crime…propel[ling] their men into aggressive action which substitutes for their own direct action’.[1] This essay will attempt to explore the extent to which this statement is accurate in regards to the female characters in Macbeth, namely Lady Macbeth herself and the witches; as well as looking at to what extent Macbeth has control over his decisions and the crimes he commits. A crime is ‘an action or omission which constitutes an offence and is punishable by law’.[2] In the Elizabethan era, a crime such as treason would have been punishable by death. This essay will explore the relationship between crime and sex (taken to mean gender) in Macbeth. Theatre and the law have a long history of being interlinked, and the criminalization of many aspects of the theatre was at its peak in Shakespeare’s contemporary society. In addition to this underlying sense of misdemeanor accompanying plays, Macbeth was initially performed in 1606, shortly after the publication of King James’s Daemonologie in 1603.[3] In this text, he claims witches are guilty of ‘treason against God’[4] and it did not take long before witchcraft became ‘the quintessential representation of the dangerous power of women’.[5] Due to this, there is already a clear link between Macbeth and crime, however arguably the play centers around a question of guilt and who is responsible. It could be argued that if Lady Macbeth was male, she would not have needed to manipulate Macbeth and could simply have killed Duncan herself. When a woman got married in Shakespeare’s era, she essentially became the property of her husband, however in doing so she gains an odd power over him as Rackin argues, ‘a woman’s subjugation to her husband’s will was the measure of patriarchal authority and thus of his manliness…paradoxically their power over women made men vulnerable to women’.[6] This statement suggests that Lady Macbeth could be seen as the bearer of the most guilt as she exploited Macbeth in order to advance her social standing, under the guise of helping him.

Lady Macbeth has an interesting role in Macbeth acting as Shakespeare’s instigator to spur Macbeth into action, yet to what extent she is responsible for the crime that occurs remains to be seen. McCarthy suggests that she is exploiting Macbeth, ‘the very prospect of murder quickens an hysterical excitement in her…which Macbeth can give her and which will be an “outlet” for all the repressed desires he cannot satisfy’.[7] If this is the case Traub is correct to claim Macbeth is ‘victimised by the sexual power wielded by commanding and evil women’, as it seems Lady Macbeth is using her influence as his wife to manipulate him into doing her bidding.[8] As Lady Macbeth does not commit the crime herself, some critics have likened her character to the ‘heroes’ collaborators or stage managers rather than independent centres of self interest’.[9] This could be due in part to her gender which would have restricted her from moving in certain spheres that her husband had free range of. It could be argued then that her guilt is conditional on that of her husband, if she cannot cajole him into committing the crime in the first place, then she would bear no guilt. Furthering this idea, it could be a suggestion of Lady Macbeth as the ultimate Victorian wife, whose ‘ambition was all for her husband’ with no regard to the consequences for herself.[10] Bamber sees Lady Macbeth as a much more selfish character and claims that her ‘evil is inseparable from [her] failures as a woman’ and links the idea of dissatisfaction with gender roles to Lady Macbeth’s traitorous ideas.[11] This idea of gender playing a role in crime is echoed by Rackin who states, ‘women were able to trouble the masculine historical narrative and sometimes subvert it, but the narrative itself remained as a given’.[12] If we take this to be true, Lady Macbeth is absolved of all sin. This idea of a male dominated narrative is echoed in Lady Macbeth’s cries of ‘unsex me here!’, where she essentially renounces her capacity for female sentiment for the spirit of murder.[13] The idea that in order to commit the crime she must first be released from the constraints of her womanly sensibilities is in keeping with the public attitudes towards women at the time. The rapid descent into insanity that Lady Macbeth experiences is ‘rehears[ing] a prototypically modern conception of universal femininity, proving once again in her madness that killing is antithetical to a woman’s essential nature’.[14] Through her obsession with washing her hands and Shakespeare’s use of the line ‘will these hands ne’er be clean?’, Lady Macbeth acts out her own complicity in the crime and shows that she has been tainted by it all the same, despite only playing an indirect role.[15] By encouraging Macbeth to murder Duncan, she becomes part of the criminal act and is overwhelmed by the guilt which she feels.

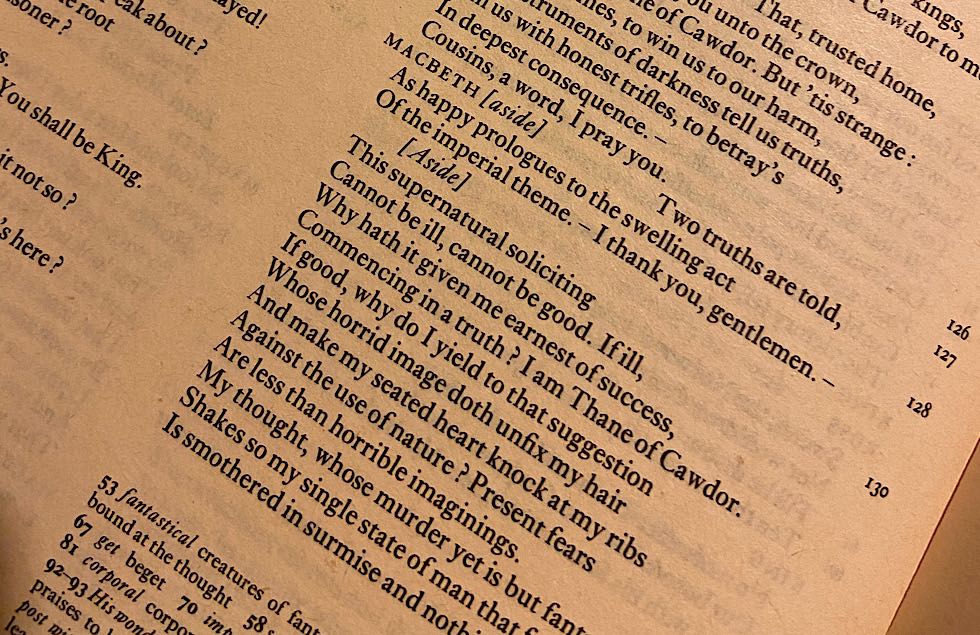

The other strong female presence in the play is the ‘weird sisters’ who are identified as witches.[16] Following the Reformation there was increased religious conflict and many people began to question their beliefs in God and magic, which lead to many women being prosecuted throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[17] There was a fixation on the darker side of female sexuality and there was a pervasive link between femininity and witchcraft.[18] It seems as though in reference to crime, ‘the question of a woman’s sexual constancy is raised with surprising frequency’.[19] When Macbeth and Banquo stumble upon three people who ‘should be women, / and yet your beards forbid me to interpret / that you are so’ the audience of the time would have known that some illicit activities were in the making.[20] Shakespeare’s inclusion of the witches is a clear indication that crime was highly common in his contemporary society. Speculations about witches included the idea that they used ‘words and devilish contacts to harm or occasionally murder from a distance’, which is reflected in Macbeth as the prophecy ‘thou shalt be king hereafter!’[21] By proclaiming this in such a manner, it could be argued that this weighs on Macbeth’s mind and plays a role in the murder of Duncan. To this extent, part of the guilt of the crime rests upon their shoulders too. There are many types of havoc which are traditionally associated with the ‘witches’ maleficium: interference with livestock and weather’, which are both shown in the play.[22] During the storm Duncan’s horses are claimed to ‘eat each other’ and there is general chaos for illicit activities to occur, something that would stereotypically have been associated with the actions of witches.[23] Shakespeare also links the weird sisters to the crime of infanticide, from the line ‘finger of birth-strangled babe / ditch deliver’d by a drab’.[24] By doing this, he is representing the prevailing public attitude towards women that subverted traditional gender stereotypes, categorizing them as evil witches.

Macbeth is arguably initially a victim within this play, convinced to commit treason by his wife before going mad with guilt. There is a tremendous amount of gender pressure on Macbeth to succumb to his wife’s demands and taunts, ‘when you durst do it, then you were a man’.[25] Masculinity was a very important construct during this era, and so to make a comment such as this would have been seen as highly insulting, and would not have given Macbeth an option to back down from the challenge. Lady Macbeth ‘block[s] the heroes’ exits from the world of men’ and resigns him to committing the crime, thereby absolving Macbeth of guilt for this initial crime. From this point onwards, Macbeth begins to go on a murderous rampage and eventually gains the courage to kill by himself ‘thou shalt not live’.[26] Once he has committed the first crime, the others seem easier in comparison and Macbeth ends up committing the mortal sin of murder on three separate occasions. This rapid descent into madness may be Shakespeare’s commentary on how crime always leads to a fall. What started as Lady Macbeth’s ambition to have a higher social standing has resulted in mass murders and warfare.

Within the play, there is a clear argument between the natural and the unnatural, epitomized by the Banquo’s line ‘cursed thoughts that nature / gives way to in repose’, suggesting that the natural order of the world has been thrown off as Macbeth’s murderous intent grows.[27] This could potentially be Shakespeare attempting to portray the murders as crimes against nature itself, as they are so deeply dissonant with human morals. Macbeth begins to play God, and his natural world begins to fall apart around him as his obsession with having murdered sleep, ‘nature’s second course, / chief nourisher in life’s feast’, grows and it becomes apparent that the attempt to usurp the natural order of the world has backfired.[28] This is reinforced by the mention of the storm that the witches have played a part in creating. The ‘lamentings heard i’ the air; strange screams of death’ following the murder of Duncan could represent the world crying out in anguish at the crime Macbeth has committed, suggesting that it not only impacts individuals but the entire world in which the play is set.[29] Furthermore, the line ‘’tis day, / and yet dark night strangles the travelling lamp’ suggests a sudden onslaught of depression and uncertainty due to the connotations of darkness.[30] Shakespeare may be using pathetic fallacy to reflect the dire situation that the Macbeth family have found themselves in. The use of the violently emotive ‘strangles’ exacerbates this sense of unease and suggests that by committing treason, Macbeth has killed daylight and happiness forevermore. The audience is drawn in to sympathise with the fear that the characters on the stage are feeling as a result of this, and the true severity of the crime begins to be realized.

In conclusion, there is obviously a clear intersection between Macbeth and crime as it was such a common occurrence in Shakespeare’s everyday life, however when relating it to issues of gender it becomes more of a question of guilt and remorse. Opinions towards the supernatural were very skeptical, and there was an air of discomfort within the British nation due to the recent ascension of King James, a Scotsman, to the throne. To this end, it makes sense to place some of the blame for the crimes committed within the play upon the shoulders of the weird sisters, the easy scapegoats. However, there are many other contributing factors that caused the murder of Duncan including the exploitation of Lady Macbeth’s sexuality to exert control over her husband and the weakness of Macbeth’s resolution, as had he just refused his wife’s request, no crime would have been committed in the first place. There are many suggestions of the links between Lady Macbeth and the witches, most notably the line ‘take my milk for gall’ which is reminiscent of the evil spirits that feed off of the witches.[31] Thomas Neely suggests that Lady Macbeth and the witches have ‘parallel role[s] as catalysts in Macbeth’s actions’, a statement that rings true when considered through the play as a whole as Macbeth required a great deal of convincing to commit the initial crime, implying that he would not have instigated it without the pressure from these external factors.[32] It appears as though Shakespeare thinks of the crimes committed not only as an individual slight, but as an action with dire consequences for the whole world that the play is set in due, which is potentially a commentary on his thoughts concerning murder being a crime against the fibre of nature. Lady Macbeth and the witches both have a large influence over the crime, however whilst the weird sisters can have a direct involvement through spellcasting, Lady Macbeth is only afforded the power of persuasion over Macbeth and can control from a distance. In some respects, this gives a higher power to the female characters as they can mastermind the crime without having to get their hands dirty. Bamber states that ‘the woman is defined in terms of her success or failure in the masculine-historical struggle for power’ and from this, Lady Macbeth can be understood as taking as much responsibility for the crime as her gender permits her to, in order to advance her status the only way she knows how to.[33]

Bibliography

Bamber, Linda, Comic Women, Tragic Men: A Study of Gender and Genre in Shakespeare (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982)

King James I, ‘Deamonologie: In Forme of a Dialogie’, Project Gutenberg (2008) <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25929/25929-pdf.pdf> [accessed 09 January 2019]

Mawby, Rob, ‘Sex and Crime: The Results of a Self-Report Study’, The British Journal of Sociology, 31.4 (1980), 525-543

McMahon, Vanessa, Murder in Shakespeare’s England (London: Hambledon and London, 2004)

Rackin, Phyllis, ‘Dated and Outdated: The Present Tense of Feminist Shakespeare Criticism’, Presentism, Gender, and Sexuality in Shakespeare, ed. by Evelyn Gajowski (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp.49-62

Rackin, Phyllis, ‘Dated and Outdated: The Present Tense of Feminist Shakespeare Criticism’

Rackin, Phyllis, ‘Engendering the Tragic Audience: The Case of Richard III’, in Shakespeare and Gender: A History, ed. by Deborah E. Barker and Ivo Kamps (Guildford: Verso, 1995), pp.263-282

Rackin, Phyllis, Shakespeare and Women (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Shakespeare, William, Macbeth, ed. by W.J. Craig (London: Henry Pordes, 1978)

Thomas Neely, Carol, Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture (London: Cornell University Press, 2004)

Traub, Valerie, ‘Jewels, Statues and Corpses: Containment of Female Erotic Power in Shakespeare’s Plays’, in Shakespeare and Gender: A History, ed. by Deborah E. Barker and Ivo Kamps (Guildford: Verso, 1995), pp.120-141

Unknown, ‘Crime’, Oxford Living Dictionaries (2019) <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/crime> [accessed 09 January 2019]

Unknown, ‘King James VI and I’s Demonology, 1597’, British Library (n.d.) <https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/king-james-vi-and-is-demonology-1597> [accessed on 09 January 2019]

References

[1] Rob Mawby, ‘Sex and Crime: The Results of a Self-Report Study’, The British Journal of Sociology, 31.4 (1980), 525-543 (pp.526-527).

[2] Unknown, ‘Crime’, Oxford Living Dictionaries (2019) <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/crime> [accessed 09 January 2019].

[3] Unknown, ‘King James VI and I’s Demonology, 1597’, British Library (n.d.) <https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/king-james-vi-and-is-demonology-1597> [accessed on 09 January 2019].

[4] King James I, ‘Deamonologie: In Forme of a Dialogie’, Project Gutenberg (2008) <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25929/25929-pdf.pdf> [accessed 09 January 2019] p.61.

[5] Phyllis Rackin, ‘Engendering the Tragic Audience: The Case of Richard III’, in Shakespeare and Gender: A History, ed. by Deborah E. Barker and Ivo Kamps (Guildford: Verso, 1995), pp.263-282 (p.268).

[6] Phyllis Rackin, ‘Dated and Outdated: The Present Tense of Feminist Shakespeare Criticism’, Presentism, Gender, and Sexuality in Shakespeare, ed. by Evelyn Gajowski (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp.49-62 (p.57).

[7] Phyllis Rackin, Shakespeare and Women (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), p.120.

[8] Valerie Traub, ‘Jewels, Statues and Corpses: Containment of Female Erotic Power in Shakespeare’s Plays’, in Shakespeare and Gender: A History, ed. by Deborah E. Barker and Ivo Kamps (Guildford: Verso, 1995), pp.120-141 (p.120).

[9] Linda Bamber, Comic Women, Tragic Men: A Study of Gender and Genre in Shakespeare (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982), p.92.

[10] Rackin, Shakespeare and Women, p.120.

[11] Ibid., p.2.

[12] Rackin, ‘Dated and Outdated: The Present Tense of Feminist Shakespeare Criticism’, p.57.

[13] William Shakespeare, Macbeth, ed. by W.J. Craig (London: Henry Pordes, 1978), I.5.391.

[14] Rackin, Shakespeare and Women, p.124.

[15] Shakespeare, V.1.2167.

[16] Ibid., III.3.131.

[17] Vanessa McMahon, Murder in Shakespeare’s England (London: Hambledon and London, 2004), p.17.

[18] Ibid., p.111.

[19] Bamber, p.3.

[20] Shakespeare, I.3.145-147.

[21] Ibid., I.3.151.

[22] Carol Thomas Neely, Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture (London: Cornell University Press, 2004), p.58.

[23] Shakespeare, II.4.968.

[24] Ibid., IV.1.1577.

[25] Shakespeare, I.7.528.

[26] Shakespeare, IV.1.1647.

[27] Shakespeare, II.1.577-578.

[28] Ibid., II.2.698-699.

[29] Ibid., II.3.825.

[30] Ibid., II.4.954-955.

[31] Ibid., I.5.398.

[32] Thomas Neely, p.57.

[33] Bamber, p.135.