‘Half in love with easeful death’: Analysing the erotics of death in selected sonnets and Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

This essay will examine the erotics, portrayal and personification of death in some selected sonnets by William Shakespeare and in his Romeo and Juliet. Whilst they were both written within the same time period, and as such will have almost identical contextual and cultural influences and will have been intended for the same contemporary audience, the ways in which death is portrayed varies. This is likely due to the differing genres- sonnets are traditionally poems used to express love therefore have a strict form that they must adhere to; whilst Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy written for a stage, and as such has a more flexible form and the content can be adapted to suit the scene. This essay will explore the changing ways in which Shakespeare links death to sex, violence, emotions and fate in order to elicit this romanticised idea of death within the reader/audience.

Sex and death are closely interwoven throughout both texts. This may be due to the time period in which Shakespeare was writing, where a marriage was not official until it had been consummated. There has been speculation that the link was so popular during the Elizabethan period due to the print named De Morte & Amore which was made popular by Emblematvm Libellvs (Andrea Alciati, 1534). This showed a close relationship between Cupid and Death which culminated in them mixing up their respective arrows and chaos ensuing as a result, but aimed to make a statement about the complexities of life and how unexpected events can transpire.[1] In Romeo and Juliet death is personified as having ‘deflow’red’ (IV.5.63) Juliet, which is an interesting choice of language as it personifies death as an evil being, a violent lover that simply takes what he wants.[2] The use of the floral reference here is interesting as virginial brides were often referred to as gardens during the Renaissance, so the fact that Juliet has been ‘deflow’red’ (IV.5.63) furthers this sense of the sexual brutality and forcefulness of death.[3] In the final scene of the play, Shakespeare draws a strong parallel between death and sex with the line ‘a light’ning before death’ (V.3.90). This is defined as an almost exhilarating feeling, which Shakespeare may have intended to be a play on male ejaculation, thus linking them due to the sense of climax.[4] Shakespeare continues with the line ‘I will lie with thee tonight’ (V.1.34) which again draws on the idea of the pair laying in the marital bed together, thus drawing further parallels. In the sonnets however, the attitude towards sex when linked to death is much more negative, ‘the expense of spirit in a waste of shame | is lust in action […] perjured, murderous, bloody’ (Sonnet 129, line 1-3).[5] The ‘spirit’ here is a reference to semen, which was seen as one of the vital life essences, and so by losing them you were essentially losing some of your vitality and thus your life. The use of words such as ‘murderous’ which has exclusively negative connotations make it clear to the reader that this is a bad action, and should only be done to achieve a worthwhile goal, such as having children.

The link between violence and death is a lot subtler in the sonnets than in Romeo and Juliet, which may again be down to the differing genres. Mercutio and Paris both die violent deaths, Mercutio even cursing the two families as he dies, ‘A plague a both houses’ (III.1.91). By doing this, Shakespeare may be showing the clumsiness of violence, as the stage directions are brief ‘Tybalt stabs Mercutio’ (III.1.88) and there is not much attention paid to it. If this was not enough, Shakespeare reminds us of the irony of the situation with the line ‘my only love sprung from my only hate’ (I.5.251). The hugely emotive language used here emphasises the ridiculousness of the scenario, and the intensity of the two opposing emotions. In the sonnets however, time is seen as a more violent character working in co-operation with death, ‘Time’s fell hand defaced […] brass eternal slave to mortal rage’ (Sonnet 64, lines 1-4). The use of the word ‘eternal’ shows the permanence of death and almost highlights the inevitability of it, as well as emphasising the vulnerability of everything due to the use of the word ‘brass’, a material that is resilient and strong.[6]

Shakespeare links death very closely with strong emotions in both texts. In some ways, he presents death almost as a more emotional event than the act of love with phrases such as ‘bears it out even to the edge of doom’ (Sonnet 116, line 12)[7]. The use of the word ‘doom’ gives the sense of the inevitability of death, how inescapable it is. The fact that love is still trying to continue to the bitter end creates a bittersweet tone to the sonnet, as it shows no matter how hard we try or how pure love is, ultimately it will not make a difference as you will be separated (at least temporarily) in death whilst one lover lives on. In sonnet 18 a differing sense is created through the line ‘so long lives this, and this gives life to thee’ (sonnet 18, line 14), implying that whilst death is unavoidable, through the sheer permanence of poetry, ‘the eternal lines to time thou grow’st’ (sonnet 18, line 12), the love which the couple share can live on and nothing will ever be able to destroy that.[8] The use of ‘thou grow’st’ is also particularly interesting as the idea Shakespeare plants in the reader’s head is one of love developing more over time, even after death. In such a way, it could be argued that death is an ultimately uniting force for love and not a negative thing at all. In Romeo and Juliet death is seen more as an escape or sacrifice; however it is clear that whilst the young lovers’ ultimate demise was tragic, it brought about a positive change in society and ultimately united them as they never could have been in life. The references to ‘friendly drop | […] die with a restorative’ (V.3.163-166) show how Juliet sees her suicide as the only way to be with Romeo and the positive language used shows her true conviction of this idea; ‘restorative’ is so contradictory to the idea of death as it implies ideas of revitalisation and repair and yet it proves that death is ultimately the only way for the lovers to be together.

Shakespeare interweaves the sense of fate and inevitability of death into both texts, which creates a sense of hopelessness and helplessness in the intended audience. Especially in Romeo and Juliet, there is a huge amount of foreshadowing and dramatic irony which serves to emphasise these feelings of dread and foreboding. Some critics have speculated however, that in Romeo and Juliet, whilst ‘the verbal emphasis is frequently on fate; […] the logic of the play seems to be […] chance’.[9] This is frequently touched upon within the play, ‘lamentable chance’ (V.3.146) and ‘untimely death’ (I.4.109); however Shakespeare seems to be placing a much heavier influence on fate right from the opening, calling the pair ‘star-crossed lovers’ (I.1.6) and referring to their love as ‘death-marked’ (I.1.9). By setting it up in the prologue, fate is already inextricably interwoven with the love they share and the inevitability of their demise almost becomes more detached and less emotional through this. In the sonnets there seems to be almost a lack of pathos due to the factual way death is described, ‘Time will come and take my love away’ (sonnet 64, line 12) and ‘to love that well, which thou must leave ere long’ (sonnet 73, line 14)[10]. The use of the modal verbs within these sentences creates a tone of determination and inescapability to death and the lack of emotive language again distances the reader from the trauma usually associated with death.

In conclusion, Shakespeare presents the ‘erotics of death’ in many different ways throughout the two texts. This is largely due to the differing genres leading to varying requirements for the presentation of the relationships between love and death, however in both Shakespeare manages to portray many different attitudes towards the final act of dying. At different points within the sonnet collection and the play, Shakespeare shows death to be closely related to sex, either as a moment of climax or as a necessity for continuing life afterwards; the links it shares with violence due to the extremity of both ideas; the emotional responses associated with loss and finally how a lack of pathos can be created due to the fundamentality of death. This is due to the fact that no matter how hard anyone tries to escape death, it will always occur eventually, but Shakespeare also creates a sense of hope that tragic events can lead to positive consequences due to the everlasting impact each and every human has on the world simply by being alive.

Bibliography

Primary texts:

Shakespeare, William, Assorted Sonnets, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)

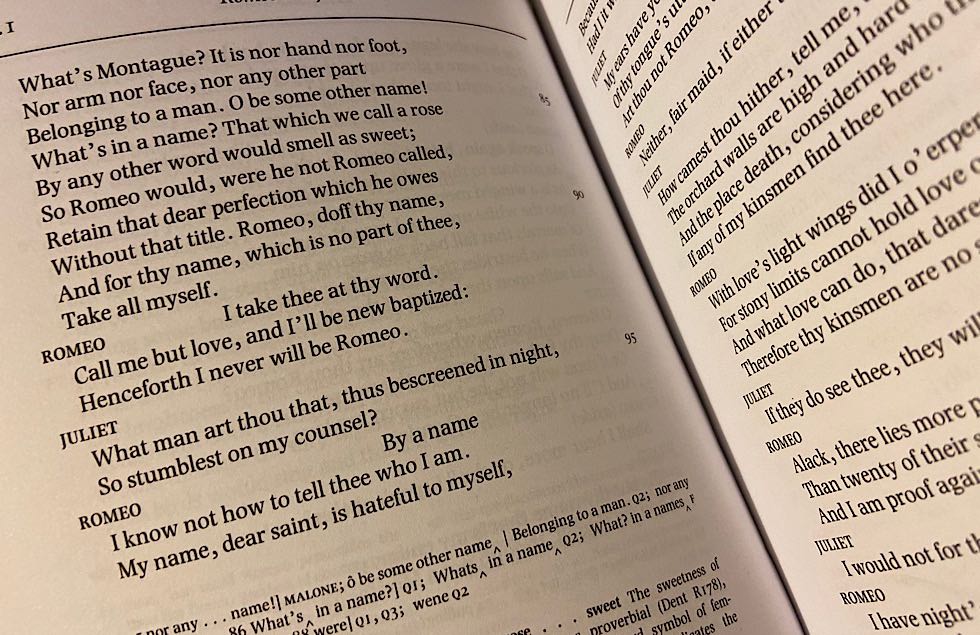

Shakespeare, William, The Oxford Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet. New York (2008): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 322.

Secondary texts:

Burrow, Colin, The Complete Sonnets and Poems. New York (2002): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 412.

Levenson, Jill L., The Oxford Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet. New York (2008): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 343.

MacKenzie, Clayton G., ‘Love, sex and death in Romeo and Juliet’, English Studies, 88 (2007), pp. 22-23

Spencer, T. J. B., William Shakespeare. Harmondsworth (1968): Penguin. pp.7-44

References

[1] Clayton G. MacKenzie, ‘Love, sex and death in Romeo and Juliet’, English Studies, 88 (2007), pp. 22-23

[2] William Shakespeare, The Oxford Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet. New York (2008): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 322.

[3] Colin Burrow, The Complete Sonnets and Poems. New York (2002): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 412.

[4] Jill L. Levenson, The Oxford Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet. New York (2008): Oxford University Press Inc., pp. 343.

[5] William Shakespeare, ‘Sonnet 129’, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)

[6] William Shakespeare, ‘Sonnet 64’, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)

[7] William Shakespeare, ‘Sonnet 116’, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)

[8] William Shakespeare, ‘Sonnet 18’, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)

[9] T.J.B. Spencer, William Shakespeare. Harmondsworth (1968): Penguin. pp.7-44.

[10] [10] William Shakespeare, ‘Sonnet 73’, in Star-Cross’d Lovers: Reader I (Cardiff: Cardiff University, 2016)